So what is speed bump punctuation? The term occurred to me when Judith a writing coach commented, “The semicolon in a sentence slows the reader more than a comma.” The comment resonated with me, producing images of speed bumps in sentences. Speed bumps determine how fast vehicles drive where reduced speed is desired. Then cars speed along thoroughfares, covering similar distances at a quicker pace. Similarly, punctuation sets the pace as a reader plows through a novel. In dialogue and fiction, punctuation and sentence length affect pace and tension. Many writers master this pace-setting skill in narrative better than in dialogue.

“I find it difficult to write snappy, believable dialogue” is a comment frequently heard in critique sessions. Good dialogue and narrative require the proper application of the comma, colon, semicolon, em dash, period, exclamation point, and question mark, setting pause length and full stops—the readers’ speed bumps and stop signs. Learning to master these common marks in narrative is hard enough, then dialogue adds one more: ellipsis or suspension point. All the marks help to show a character’s actions without telling it. The problem seen most often in critique session is the use of an em dash as opposed to an ellipsis and vice versa. This post, labeled Part 1, covers the ellipsis and suspension point. My next post, Part 2 in this blog series, examines the use of the M-dash (em dash) in dialogue. Part 3 explores the use of em dash in narrative fiction and nonfiction, while Part 4 explores the N dash (en dash), including the many applications that require this unique dash.

Style Manuals Don’t Always Agree

Manuals of style often differ on how and when to apply these punctuation marks. This post references the Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS). One of the most widely used guides, CMOS lists standards for writing in commercial and academic publishing. Chicago is the preferred style of print publishers in both fiction and nonfiction. Dana Sitar’s post in The Write Life blog provides a comprehensive list of style manuals and helps writers find the best guide for their work. Pick a style guide and follow it. Never fail to be consistent with the rules you adopt.

Ellipses Defined

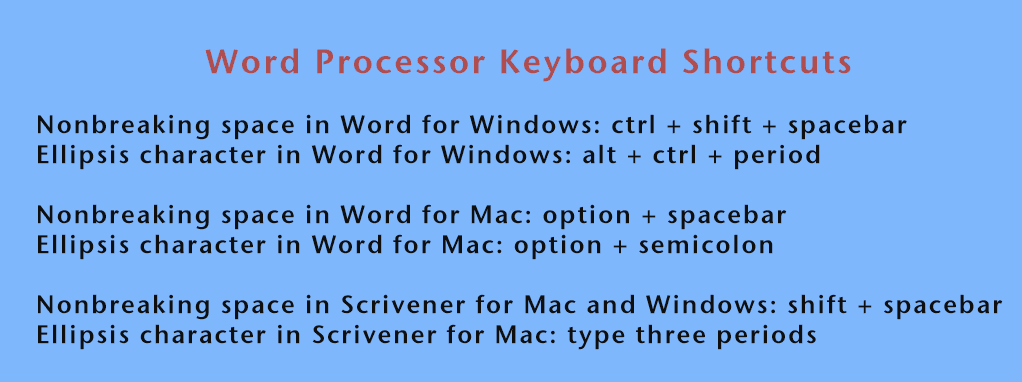

An ellipsis is a punctuation symbol with three periods. You may use either the ellipsis character ( … ) or the CMOS style of three spaced periods ( . . . ). If you use the CMOS version, nonbreaking spaces are required to keep the periods together, so the word processor never breaks the symbol in the middle of the three dots. I favor the single-glyph three-dot ellipsis character because it’s essentially a single keystroke on word processors (Unicode 2026). Pick a style and don’t deviate. Put spaces on either side of the ellipsis, except when the ellipsis is adjacent to a quotation mark. In that case, close it up.

An Ellipsis Points in Formal and Scholarly Nonfiction

Per the CMOS, an ellipsis signals the omission of a word, phrase, line, or paragraph of a quoted passage considered irrelevant to the discussion at hand. Chicago style indicates the omissions with three spaced periods, calling these points (or dots) ellipsis points. In formal and scholarly nonfiction writing, ellipses have a single function to show exclusion.

My focus in this post is narrative nonfiction, memoir, and the like, so I’ll limit my discussion of ellipsis points to an example. The following text come from CMOS and provides some insight using Emerson’s essay “Politics” that reads:

The spirit of our American radicalism is destructive and aimless: it is not loving; it has no ulterior and divine ends; but is destructive only out of hatred and selfishness. On the other side, the conservative party, composed of the most moderate, able, and cultivated part of the population, is timid, and merely defensive of property. It vindicates no right, it aspires to no real good, it brands no crime, it proposes no generous policy, it does not build, nor write, nor cherish the arts, nor foster religion, nor establish schools, nor encourage science, nor emancipate the slave, nor befriend the poor, or the Indian, or the immigrant. From neither party, when in power, has the world any benefit to expect in science, art, or humanity, at all commensurate with the resources of the nation.

Short passages from the full text follow.

The spirit of our American radicalism is destructive and aimless: . . . On the other side, the conservative party . . . is timid, and merely defensive of property. . . . It does not build, nor write, nor cherish the arts, nor foster religion, nor establish schools.

Note the four dots indicate the omission of the sentence’s ending. Also, capitalize the first word (it) after an ellipsis when a new grammatical sentence begins.

The spirit of our American radicalism is destructive and aimless: . . . . On the other side, the conservative party . . . is timid, and merely defensive of property. It does not build, . . . nor cherish the arts, nor foster religion.

Note the four-dot ellipsis (the last dot, a period, indicates missing text and sentence termination before another sentence begins) after aimless and the colan (punctuation present in the original document) before the ellipsis after build.

Have you had a chance to look at the example beginning “The spirit of our American radicalism . . .”?

Note that no space intervenes between a final ellipsis point and a closing quotation mark. And the question mark is outside the quote. The example shows a deliberately incomplete sentence.

Everyone knows that the Declaration of Independence begins with the sentence “When, in the course of human events . . .” But how many people can recite more than the first few lines of the document?

Three dots mark the end of a quoted sentence deliberately left grammatically incomplete with no sentence to follow. Also, put no space before the closing quote.

Suspension Points for Narrative Nonfiction and Memoir

In narrative nonfiction and memoir, CMOS calls the three periods suspension points because the symbol indicates breaks in thought in the middle of dialogue. Suspension points, referred to as points or dots in CMOS, replace the missing text which implies a pause or speech that trails off. CMOS limits the three-dot suspension punctuation for a pause to dialogue but not in the narrative text since it isn’t spoken. When appearing in the middle of dialogue, style requires a space before and after the symbol (space…space). But if placed at the end of the dialogue, CMOS eliminates the space before the closing quotes or before the punctuation and closing quotes to show the speech faded away. Suspension points suggest faltering or fragmented speech in dialogue, indicating confusion or insecurity. In the examples below, note the relative position of the suspension point symbol and other punctuation.

“I … I … that is, we … yes, we must escape!”

“The plane … oh my God! … it’s crashing!” cried Bettie.

“But … but …,” said John.

The breaks show faltering or fragmented speech accompanied by confusion or insecurity using the CMOS version of suspension points.

“I guess …” she clicked around the computer screen, vainly searching for the right link. “Looks like … I think … I misplaced the new version.”

“Sorry, this is really …” She couldn’t finish. The required period to indicate the end of the sentence with a tag absent is not used.

This text shows a flustered presenter. In this dialogue, the suspension points, the single-glyph, three-dot, computer-driven character depicts hesitation and a sentence drawn out. Note, the style eliminates any terminal punctuation (in the form of a period) when the suspension points end a sentence. The standard comma is optional when a dialogue tag follows, but many writers think it looks funny, so you can leave it off, but be consistent. However, a question mark or exclamation point can follow the suspension point symbol if the dialogue dictates.

“Sorry, this is really …,” she said becomes “Sorry, this is really …” she said. The required comma to indicate the end of dialogue with a tag present can be added but is not necessary.

She couldn’t find the correct file. “What the …?”

Notice that there are spaces on either side of the suspension points within a sentence, but not at the end of a sentence or before the full stop punctuation mark.

A Super Subtle Difference

Suspension points appear in creative nonfiction dialogue when the speaker hesitates for a reason internal to the speaker. These breaks in dialogue come from a speaker’s emotional state, such as fear, mental confusion, embarrassment, concern, shock, or fright. The speaker chooses to make the breaks. However, if an action, a situation, or a force external to the speaker causes a change in the flow of dialogue, CMOS style requires the use of an M-dash (em-dash) and not suspension points. In this case, the speaker’s dialogue is interrupted and not confused. That subtle difference distinguishes suspension points from an em-dash and is the topic in Part 2 of this three-blog sequence.

In Summary

There are three ways to create ellipses or suspension points: typing three periods with non-breaking spaces, entering the single-glyph three-dot computer-driven ellipsis character with a keyboard shortcut, or automatically when the author types three periods in word-processing software. I recommend using the latter two because it’s fast, looks good, and is harder to mess up. If you’re self-publishing, you can leave it that way. If you’re submitting for traditional publication, find out whether your publisher has a preference and do it that way.

The rules for ellipses (suspension points) in nonfiction differ slightly from those in fiction. In fiction, the symbol signals a hesitation or trailing-off of speech. But in nonfiction, they indicate omissions from quoted material. If you’re writing a memoir or other narrative nonfiction, use suspension points as you would in fiction pieces.

Typos lead to mistakes with ellipsis and suspension points. Writers use varying numbers of dots, spaced or not, indiscriminately throughout a document. Four or five spaced dots here, three unspaced dots there, and occasionally only two. Also, there is never a call for four-dot suspension points in fiction or narrative nonfiction. The second error, using suspension point where the text content demands an M-dash, I address in the Part 2 blog.

I’m always interested in my reader’s projects. What are you working on? Let me know here. Leave a comment and sign up for a short monthly newsletter so you never miss an informative post.

1 thought on “How to Master Speed Bump Punctuation—Part 1: Ellipsis in Dialogue”

Thanks for the detailed explanation. I’ve often struggled with punctuation in dialogue so it’s good to know a resource to go to for confirmation.